Last week, with little fanfare, the UK Government announced its ten-point plan for a “Green Industrial Revolution”. Although it falls far short of Extinction Rebellion’s demand to decarbonise by 2025, the plan nevertheless sounds impressive at first glance, including commitments to phase out sales of new petrol and diesel cars and vans, and supply all of the UK’s electricity needs from offshore wind, by 2030. Such policies are needed and represent a step forward. However, the headlines hide the inadequacy and lack of ambition of the Government’s programme. As the week has gone on and the announcement held up to greater scrutiny, more and more experts and analysts have pointed out the shortcomings of the programme. The Green Industrial Revolution is little more than greenwash – but with predictably little analysis from mainstream media outlets, it is having the desired effect of neutralising the environmental question.

Here are five reasons why the Green Industrial Revolution is in fact greenwash...

1. The plan does climate action on the cheap

Let’s start with the money. The plan calls itself the “Green Industrial Revolution”, borrowing from Labour’s 2019 election manifesto. However, whereas Labour in 2019 were pledging £400 billion over five years, the Government is proposing a one-off injection of £12 billion, topped up with uncertain private-sector investment. To put the £12 billion in context, UK GDP in 2019 was £2.17 trillion – making the investment equal to 0.5% of GDP. By contrast, Roosevelt’s New Deal – to which the Government has compared its plan – was equivalent to 40% of US GDP. Analysis has revealed that only £3 billion is new money, the remaining £9 billion having been announced previously. Is 0.1% of GDP enough to tackle the biggest crisis in human history?

2. The plan fails to achieve net zero by 2050

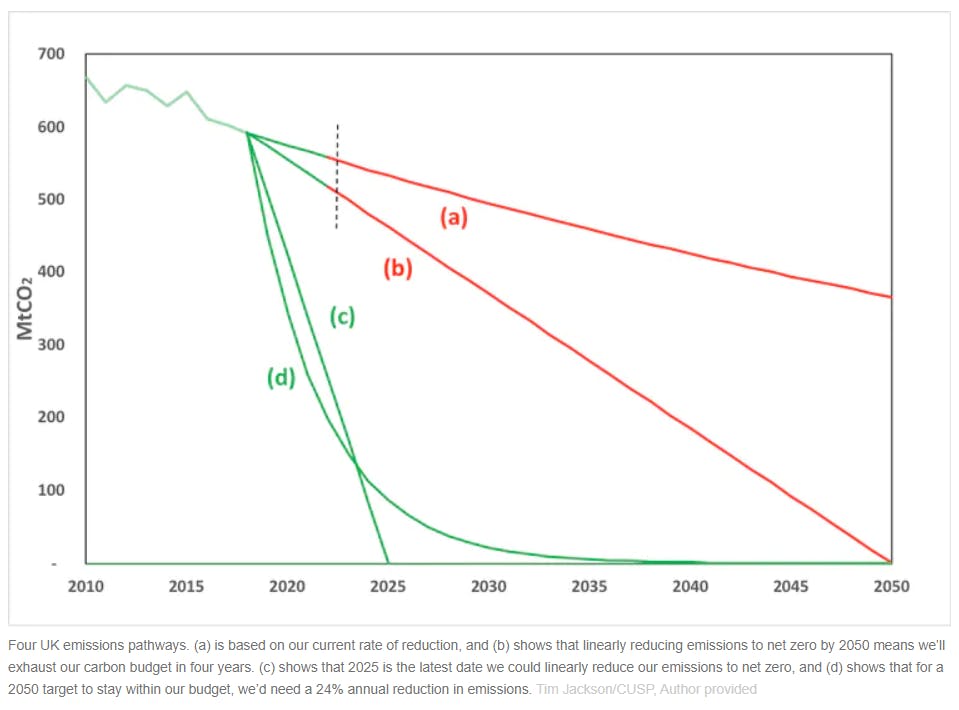

Let’s consider the premise underlying these plans. Scientists say that globally, humanity needs to reach net zero by mid-century and in May 2019 the UK committed to achieving this by law. There are several reasons why this deadline is far too late for the UK to eliminate its greenhouse gas emissions. There are both ethical and practical arguments for early decarbonisation. Firstly, early decarbonisation is a matter of justice, given that Global North countries are (a) directly (through production and consumption) or indirectly (e.g. through offshore manufacturing) responsible for the majority of current emissions, (b) responsible for almost the majority of historic emissions, which disproportionately affect Global South countries, and (c) responsible for the underdevelopment of many Global South economies. As the first country to industrialise, the UK bears particular responsibility for climate change. These are ethical reasons for the UK to decarbonise early. On a purely practical basis, to decarbonise linearly without using up our carbon budget, the UK must reach net zero by 2025. A later deadline requires decarbonisation to speed up year on year. In other words, the longer we leave it, the harder it becomes.

However, let’s approach the Green Industrial Revolution plans on the Government’s own terms – its legal commitment to achieve net zero by 2050, with no consideration of the pace with which this needs to happen. On this basis alone, the plans are not enough. Indeed, Carbon Brief calculates that the new plans are insufficient to achieve the previous target (which would see the UK Government in breach of its own laws) of reducing emissions by 80% by 2050. This puts the UK way off course on its commitments under the Paris Agreement, which seeks to limit temperature rises to two degrees above pre-industrial levels. It is important to note here that the IPCC’s 2018 report states that the Paris Agreement itself is inadequate and that warming must be limited to 1.5 degrees if we are to stand any chance of avoiding catastrophic climate effects. Warming is currently just over 1 degree above pre-industrial levels.

3. The plan is based on magical thinking

So what of the scope, ambition and logistics of the plans? The Green Industrial Revolution contains some notable and important developments, particularly the plan to ban the sale of new diesel and petrol cars and vans by 2030, ten years earlier than the Government’s original target, and the plan to generate sufficient energy to power all homes from offshore wind by 2030. Although the UK positions itself as a world leader in climate policy, the EU is considering a similar ban on new petrol and diesel cars in 2025 as part of its own (probably inadequate) European Green New Deal, while other European countries are streets ahead when it comes to renewable energy. Germany in particular expects to power all its energy needs from renewables by 2025. And while these projects sound ambitious, power and transport are only part of the path to net zero. Other major contributors to greenhouse gas emissions include construction, agriculture and business.

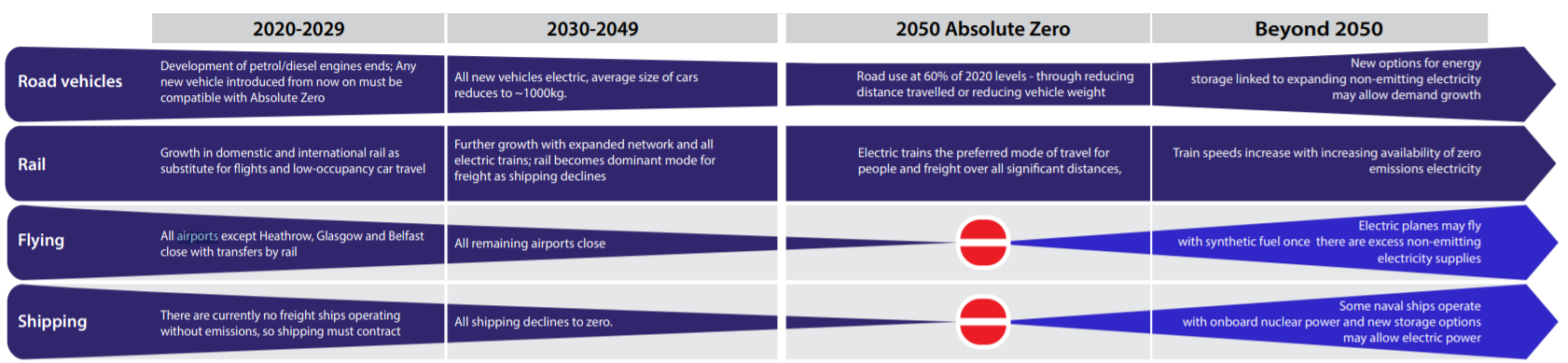

Last year’s Absolute Zero report by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council maps out a path to absolute (not net) zero in the UK by mid-century. The report, which is itself premised on timescales regarded by many experts as dangerously unambitious, spells out the need for radical changes to many areas of life. In particular, it says that air travel needs to be dramatically scaled back over the next decade, with only three airports remaining open by 2030, and entirely eliminated by 2050, unless and until zero-carbon alternatives can be developed. By contrast, the Government’s approach is based on magical thinking. Engineers say that hydrogen-powered or other zero-carbon alternatives to the conventional jet engine are not possible with currently available technology or foreseeable in the near-future. The level of investment offered in the Government’s Green Industrial Revolution is not adequate to speed up the development of these new technologies. Most big technological advances, from the internet to the iPhone, are the result of direct state R&D investment, whereas the Government’s plan is self-admittedly reliant on seemingly un-incentivised private sector innovation.

4. The plan relies on techno fixes

Similarly, there is an overemphasis on unproven techno fixes in the Government’s plans. This is not ambition, it is greenwash, designed to convince the public that radical change can be avoided through reliance on Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies which do not exist. CCS at scale is unproven and undeveloped; engineers say it is unknown whether these technologies are scalable at all. It is right that we should invest in these technologies, but we should not be relying on them. They are unlikely to be the silver bullet. The only CCS systems proven to work at scale are natural processes; photosynthesis being the best-known. This week’s announcement reheats Conservative manifesto plans formally introduced in the Budget earlier this year to plant 30,000 hectares of forest every year. This is good, but the Government’s track record is not encouraging. Previous, lower afforestation targets have not been met, with less than 10,000 hectares planted annually in recent years. And the Government’s own Climate Change Commission recommends increasing tree-planting levels to 50,000 hectares per year in an ideal scenario.

5. The plan ignores the biodiversity crisis

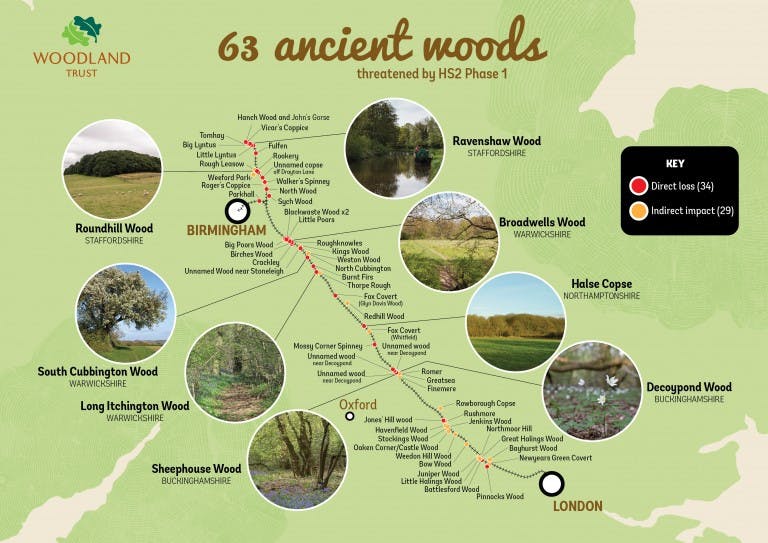

Neither do the Government’s plans address harmful policies which undermine efforts to rapidly reduce greenhouse-gas emissions and restore biodiversity. Biodiversity is mentioned in passing in the ten-point plan, with little detail provided. Yet the biodiversity crisis is as big a threat as the climate crisis – potentially bigger, given that extinct species cannot be restored, while it may prove possible in time to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. As it stands, the Government is engaged in a full-on war on biodiversity through the HS2 project, which, according to a recent report, threatens five internationally protected wildlife sites, 693 local wildlife sites, 108 ancient woodlands and 33 legally protected sites of special scientific interest. Despite being touted as a green project, HS2 will not be carbon-neutral in its 120-year lifetime. In a similarly shortsighted move, the Government in its 2020 budget announced a £27 billion investment in roadbuilding, more than twice the money announced this week for the Green Industrial Revolution (and nine times the new money allocated). This will build 4,000 miles of new road precisely at a time when we should be focusing on genuinely green public transport solutions.

All of this is a reflection of the Government’s piecemeal, magical-thinking attitude to the environmental crisis. The approach is to fiddle around the edges and hope the problem will go away, similar to the Government’s disastrous public health response to Covid-19. As is typical of Boris Johnson, announcements tend towards the eye-catching and headline-grabbing – a great propaganda exercise and enough to appease the public attitude for green policies without the need for real change, while doing almost nothing to address the scale of the problem we face. As should be expected of a Conservative Government, there is no willingness to challenge business as usual by radically restructuring our society and economy to the extent that the crisis demands. Consideration of the environmental emergency should underpin every area of policy. As well as being the only way back from the cliff-edge we face, such an approach presents huge opportunities to address social crises including fuel poverty, housing, employment, intergenerational inequality, mental health and overall wellbeing. For example, we face an escalating social care crisis, a ticking time bomb made worse by the Covid-19 pandemic. As well as being understaffed, under-resourced and based on a broken model of private provision, the caring professions are low carbon and socially necessary. With the right vision, the climate crisis is the impetus we need to vastly improve the quality of health and social care while creating thousands of jobs in a low-carbon industry.

What is new in this week’s policy announcements may sound big and radical, but the truth is these are basic measures which should have been announced many years ago. Decades of inaction now means that wholesale and rapid systems change is the only proportionate solution to the emergency we face. In particular, we need to transform agriculture, consumer production and consumption, transport and energy as well as neoliberalism’s reliance on private ownership of industry and its private-sector model of innovation. This is not an ideological statement, although the specific solutions inevitably are. The need for radical systems changes is acknowledged by the IPCC, the Government’s own Climate Change Commission, scientific bodies such as the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, even David Attenborough. Rome is burning. It’s time to stop fiddling.

We need radical climate action now. Extinction Rebellion (XR) demands decarbonisation by 2025. Our method: non-violent direct action. You can join our movement - check out our events page for XR actions in Cambridge.